(For several months I have lost myself in the thoughts of Peter Sloterdijk, a contemporary German philosopher. I need to continue to read and absorb his works, but the following is a “status report” on what I have found so far.)

UPDATE (09 May 2017): I now have had the chance to study volume 3: Foams, and re-read the trilogy, and develop some further thoughts. If you are interested, these have been assembled in a separate essay, available here on Amazon Kindle. Also, here’s a bit of my take on Foams. But even better, you should read Sloterdijk himself.

**********

“When someone tries to ‘agitate’ me in an enlightened direction, my first reaction is a cynical one: The person concerned should get his or her own shit together. That is the nature of things. Admittedly, one should not injure good will without reason; but good will could easily be a little more clever and save me the embarrassment of saying: ‘I already know that.’ For I do not like being asked, ‘Then why don’t you do something?’” – Peter Sloterdijk

The world we face is not the same as the one Peter Sloterdijk faced in 1983. That world, and Sloterdijk’s Germany especially, was split down the middle, with a belligerent Soviet Union to the east and an exceptionally deadly alliance of nations to the west. Nuclear weapons were primed and ready and held at abeyance only by the mutual recognition that destroying all life on earth would be poor sportsmanship. Germany itself was divided physically by The Wall as well as being fractured throughout in multiple ways by having been the principal aggressor in two world wars, and losers in them both. German philosophers were trying to come to terms with how their glorious and magnificent culture – the home of Goethe, Schiller, Lessing, Beethoven, and Brahms, a culture which was itself a monument to the highest ideals of humanity – could have descended so completely and quickly into the deepest inhumanity. In the bicentennial of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, Sloterdijk joined others in wondering whether it was indeed still possible to have any faith at all in reason or in any celebrated ideal of humanity.

But it is also true that the world Sloterdijk faced has not changed much in the last 30 years. The Wall is gone, and the threat of a nuclear holocaust has been replaced by comparatively smaller (though still deadly) threats. But humanist intellectuals remain skeptical of the ideals of the Enlightenment. We see now that it never really was what it pretended to be. Its authors celebrated human freedom while providing a cover story for colonial oppression and subjugation. Scientists strove mightily for a knowledge of nature while industrialists destroyed nature through forge and furnace. Its politicians aspired to democracy while creating wage slaves. The Enlightenment, it seems now, was a theater of false promises at best and a crucible of cruel mendacity at worst.

Where then do we find ourselves in our post-Enlightenment times? In Sloterdijk’s 1983 estimation, we are in an age of cynicism, or enlightened false consciousness. We all know, when we stop to think about it, that the world is not as it should be, and that we are not living as we ought to live. But even as we know this, we numb ourselves to it, and even laugh over the disconnection between what we know and how we live. “We do our work and say to ourselves, it would be better to get really involved. We live from day to day, from vacation to vacation, from news show to news show, from problem to problem, from orgasm to orgasm, in private turbulences and medium-term affairs, tense, relaxed. With some things we feel dismay but with most things we really can’t give a damn” (98-9). Our cities “have been transformed into amorphous clumps where alienated streams of traffic transport people to the various scenes of their attempts and failures in life” (118). We realize all this, and acknowledge it – and then show up at work the next day, since we feel deep down that there really is nothing to be done about it. In this way we are conscious of our situation, and unhappy about it, but resigned to it: “To be intelligent and still perform one’s work, that is unhappy consciousness in its modernized form, afflicted with enlightenment. Such consciousness cannot be dumb and trust again; innocence cannot be regained” (7).

Sloterdijk’s Critique of Cynical Reason provides a portrait of our age, and tries to find a path leading toward something – anything – more promising. But we really are in a tight spot. There is no returning to the ideals of the Enlightenment, for we have seen through them. We cannot pretend to be other than we are, and we cannot pretend that our world is any better than it really is. How then is anything other than cynicism possible for us? Any problem this difficult will require an heroic act of philosophical imagination – or perhaps, as Sloterdijk suggests, a return to attitudes less worldly, less knowing, less trapped by the conceptual snares we have laid for ourselves. As he writes in his preface, his hope is “to see the dying tree of philosophy bloom once again, in a blossoming without disillusionment, abundant with bizarre thought-flowers, red, blue, and white, shimmering in the colors of the beginning, as in the Greek dawn, when theoria was beginning and when, inconceivably and suddenly, like everything clear, understanding found its language.” He then asks: “Are we really culturally too old to repeat such an experience?” (xxxviii). By the end of his Critique, he has answered this question: “No history makes you old. The unkindnesses of yesterday compel you to nothing. In the light of such a presence of spirit, the spell of reenactments is broken. Every conscious second eradicates what is hopelessly past and becomes the first second of an Other History” (547). So there is hope for us after all. But it will take a creative act of love to make this Other History available to us. And this is as it must be: for what, other than a creative act of love, can overcome cynicism?

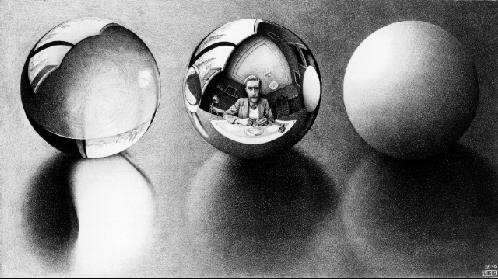

And this is where the spheres come in.

How many round things can we find? Consider first the round womb, the round sun and moon and earth; the round huts we find in round villages, whose inhabitants gather in circles around fires; the orbs of emperors and the globes of explorers; the round amphitheaters of tragedians, the domes and rounded archways of cathedrals; our very own skulls; the wheels of ox-carts and calendars, of diagrams depicting natural cycles, of heavenly bodies orbiting a central point, and of the wheel of fortune; the table of Arthur’s knights, and Jeremy Bentham’s round Panopticon; the circle drafted by Blake’s demiurge, and the sphere embodied in Plato’s demiurge; and on and on and on, as endless as the circle itself.

Spheres are more than a geometrical figure to Sloterdijk. They are enclosed social spaces whose limits are equidistant from a center. “The sphere is the interior, disclosed, shared realm inhabited by humans – insofar as they succeed in becoming humans. Because living always means building spheres, both on a small and a large scale, humans are the beings that establish globes and look out into horizons. Living in spheres means creating the dimension in which humans can be contained. Spheres are immune-systematically effective space creations for ecstatic beings that are operated upon by the outside” (I, 28). Spheres then are shelters from formless, chaotic, and inhuman forces. They can be found wherever humans are found – in the womb, in the family, among friends, in church, in nations and empires, and on maps of our world and the cosmos. One might see each social or ideological sphere as the phenotypic expression of the human need for community.

But it is important not to reduce Sloterdijk’s philosophical vision to any psychological or anthropological claim about the shapes and metaphors that homo sapiens are bound to find attractive. He is trying to provide a new hermeneutics for understanding human beings – truly, a new philosophy about what we are and what makes our lives meaningful. If we are engaged in social sciences, we have already made assumptions about our nature and the nature of our world. Those are the assumptions he is attempting to rewrite, in exactly the same way Heidegger refigured human beings by positing them as Dasein. His approach, like Heidegger’s, is phenomenological, which means that it begins and ends within human experience, broadened to include our sentiments and intuitions. We do not start with the physical world and locate ourselves as furniture within it, which is the familiar approach of the social sciences. Rather, phenomenology begins in the domain of human experience and positions our knowledge of the world within it. “Humans are beings that participate in spaces unknown to physics,” he writes, and it is only from philosophy that we can learn “how [our] passions find concepts” (I, 83; 81).

Sloterdijk’s magnum opus consists in three volumes. Spheres I bears the name Bubbles, which refers to the “microspheric units” that “constitute the intimate forms of the rounded being-in-form and the basic molecule of the strong relationship” (I, 62). These are the intimacies we first encounter in our lives, as we are born not alone but within a mother enclosing us, whose voice and body are the first sounds we encounter. The second volume’s title is Globes, which explores “a historico-political world whose models are the geometrically exact orb and the globe” (I, 64). This is basically the transition from Aristotle’s terracentric heavenly spheres to Kepler’s heliocentric elliptical orbits, from flat Eurocentric maps with hazy borders to globes. The third volume, Foam – which has yet to appear in English translation – “will address the modern catastrophe of the round world…. For Catholic Old Europeans, the essence of the Modern Age can still be expressed in a single phrase: spheric blasphemy” (I, 69-70; emphasis added). Sloterdijk explains further: “In foam worlds, the individual bubbles are not absorbed into a single, integrative hyper-orb, as in the metaphysical conception of the world, but rather drawn together to form irregular hills…. What is currently being confusedly proclaimed in all the media as the globalization of the world is, in morphological terms, the universalized war of foams” (71). Our age consists in fractures, not homogenization.

Sloterdijk’s Spheres is more like a brainwashing flood than it a patient argument for identifiable conclusions. But this is just what it must be, if Sloterdijk’s final aim is to overcome cynicism. No argument can possibly succeed – what is required instead is a radical change in vision, a conversion to newfound meaning. Spheres are above all expressions or institutions of love. He states his central thesis in the introduction to the trilogy: “I will develop, more obstinately than usual, the hypothesis that love stories are stories of form, and that every act of solidarity is an act of sphere formation, that is to say the creation of an interior” (I, 12). And “solidarity” here means, as he later explains, “the power to belong together” (I, 44-5).

I will need to read the third volume before I can get the full picture, but from the first two volumes we can anticipate where this all ends up. First, Sloterdijk’s philosophy tells that that we do not start out as atomic, self-interested individuals, but as beings whose consciousness already belongs together with others. If our lives are to be meaningfully human, they must continue to be integrated into spheres -communal, social, political, ideological, and perhaps also religious or mystical.

Second, our cultural and political efforts are to be understood by the spheres they foster or diminish. Every social form – ideally, anyway – provides “a bell jar of purpose”:

“Every social form has its own world house, a bell jar of purpose, under which humans first of all gather, understand themselves, defend themselves, grow and dissolve boundaries. The hordes, tribes and peoples, and the empires all the more, are – in their respective formats – psychosociospheric quantities that arrange themselves, climatize themselves and contain themselves. At every moment of their existence, they are forced to place above themselves, by their typical means, their own semiotic heavens from which character-forming collective inspirations can flow to them.” (I, 57)

When we forget this, we risk getting everything backwards: like Hobbes, we start thinking of social forms as instruments for advancing our own agendas, rather than as “psychosociospheric” ecosystems that sustain our lives.

Finally, if we are to overcome cynicism, we have a huge existential crisis to deal with. Our more recent history is mainly one of failing to grapple with the philosophical consequences of atheism:

“Taken in its true context, then, the great declaration of God’s death means something entirely different from what the vulgar readings of all interest groups customarily claim: understood on its own terms, it deals with the meaning of losing the cosmic periphery, the collapse of the metaphysical immune system that had stabilized the imaginary in Old European thought in a final format. … “God is dead” – what this actually means is that the orb is dead, the containing circle has burst… for the height is empty, the edge no longer holds the world together, and the picture has fallen out of its divine frame. … After the scientific attack on the harboring circle, the personal enchantment of geometry is finished. Now humans are only immanent to the outside, and must live with this difficulty.” (II, 559)

There never is any going back – that is pretty much the meaning of time. But by seeing our history and our lives in terms of Sloterdijkian spheres, we begin to see the outlines of what we require. We must begin to take ourselves more seriously than our current super-sized media allows, and beware of reducing our experiences to the dregs left behind by our drainers of culture – “No happiness is safe from endoscopy: every blissful, intimate, vibrating cell is surrounded by swarms of professional disillusioners, and we drift among them – thought paparazzi, deconstructionists, interior deniers and cognitive scientists, accomplices in an unlimited plundering of Lethe” (I, 76).

But exactly where we will end up as a result of our spherological efforts is anybody’s guess. Sloterdijk, I think, is presenting us with a new story – a fantastic and fascinating story rich with illustrations and compelling exploration – with a new vocabulary, and with a new sense of urgency for us to think along new lines. I will now throw caution to the wind and let fly an expression of my full admiration: Sloterdijk is the greatest philosopher of our times, and even, in my own estimation, the greatest philosopher since Hegel. I hope – I pray – that his works will be read and admired by later generations seeking to understand just what encouraged human beings to rethink and reorient a culture mired in nihilism.

Leave a reply to Philip Cancel reply