[What follows is a version of an address recently given at the Mountain-Plains Philosophy Conference, where a good time was had by all.]

In a lecture at the University of Munich in 1919 – the year before he died – Max Weber spoke to an audience of students about “Science as a Vocation”. His remarks are frank and clinical, describing with perfect candor the difficulties and disappointments students will face if they choose the academic life. In particular, they will have to get used to being passed over for promotion, to making only tiny contributions to their disciplines, to pressures of attracting larger and larger enrollments so as to fill up the tuition coffers, and to living generally in poverty and obscurity. Moreover, the great ideas and passion that inspired them to be scientists in the first place won’t find any expression in work they do – at least, not if they are good scientists. For while any science always carries along its own presuppositions – particularly, presuppositions of what is important, valuable, or worthwhile – science itself cannot establish anything about how we should live or what our lives should be about. “No science is absolutely free from presuppositions, and no science can prove its fundamental value to the man who rejects these presuppositions” (153). At the most, one might say, science can provide hypothetical imperatives, or connections that say “if you want this, do that”, or practical advice about the most efficient means to given ends. But it cannot give us those ends.

In a lecture at the University of Munich in 1919 – the year before he died – Max Weber spoke to an audience of students about “Science as a Vocation”. His remarks are frank and clinical, describing with perfect candor the difficulties and disappointments students will face if they choose the academic life. In particular, they will have to get used to being passed over for promotion, to making only tiny contributions to their disciplines, to pressures of attracting larger and larger enrollments so as to fill up the tuition coffers, and to living generally in poverty and obscurity. Moreover, the great ideas and passion that inspired them to be scientists in the first place won’t find any expression in work they do – at least, not if they are good scientists. For while any science always carries along its own presuppositions – particularly, presuppositions of what is important, valuable, or worthwhile – science itself cannot establish anything about how we should live or what our lives should be about. “No science is absolutely free from presuppositions, and no science can prove its fundamental value to the man who rejects these presuppositions” (153). At the most, one might say, science can provide hypothetical imperatives, or connections that say “if you want this, do that”, or practical advice about the most efficient means to given ends. But it cannot give us those ends.

When it comes to figuring out what ends we should take for our own, Weber turns to philosophy. But here again he does not expect that philosophy will establish what values we should adopt. Rather, philosophy will illuminate and make explicit what the options are, and how they fit in or do not fit in with other presuppositions we might be lugging around with us. In the end, it is up to us to establish our values:

And if you remain faithful to yourself, you will certainly come to certain final conclusions that subjectively make sense. This much, in principle at least, can be accomplished. Philosophy, as a special discipline, and the essentially philosophical discussions of principles in the other sciences attempt to achieve this. Thus, if we are competent in our pursuit (which must be presupposed here) we can force the individual, or at least we can help him, to give himself an account of the ultimate meaning of his own conduct. (151-2)

Weber recommends that if his students become teachers, they should not try to push their own values upon their students, but should lay bare the available choices and help their students to choose for themselves. (One cannot avoid hearing in this the great disillusionment stemming from Germany’s loss in WWI.)

The more general backdrop to this discussion of science and values is Weber’s recognition that his world, the modern world, is disenchanted. “One need no longer have recourse to magical means in order to master or implore the spirits, as did the savage, for whom such mysterious powers existed. Technical means and calculations perform the service. This above all is what intellectualization means” (139). But once we know the world to be disenchanted, we deprive the objects of our knowledge of the magical power required to legislate our life values. No empirical measurement of the world will tell us how things should be, as Hume famously observed. At this point, according to Weber, we are left turning to either “the transcendental realm of mystic life or into the brotherliness of direct and personal human relations” to find our values. In short: we either make the grounding of value ineffable, or else we base it upon how good it feels to be nice to other people, and we assume there’s some genuine value in that – even if we can’t demonstrate it scientifically.

Scientists who go ahead and believe that there is a supernatural order, or supernatural values, will have to pay for this extravagance with an intellectual sacrifice, according to Weber: they will have to kill off their scientific presupposition that the world is disenchanted. If they do not disown this presupposition – if intellectuals want to have the world both ways, both enchanted and disenchanted, they will be living a lie:

For such an intellectual sacrifice in favor of an unconditional religious devotion is ethically quite a different matter than the evasion of the plain duty of intellectual integrity, which sets in if one lacks the courage to clarify one’s own ultimate standpoint and rather facilitates this duty by feeble relative judgments. (155)

In other words, any scientist or intellectual of the modern age who wants to hold on to overarching values needs to come clean: either admit to having an enchanted view of the world, or sacrifice intellectual integrity.

I am interested in asking about the situation of philosophy in the dialectic that Weber proposed. I will be proposing a trilemma. Is philosophy in the same boat as science, as Weber saw it – meaning that philosophy, thoroughly applied, is an engine for thorough and complete disenchantment? Or can philosophy provide some sort of grounding for value, which Weber thought was not possible? Or, going in the opposite direction: should philosophy possibly be in the business of providing enchantment, and thereby providing overarching values? In exploring this terrain, I’ll first look at the problem of disenchantment in general terms, and then turn to two philosophers: Daniel Dennett, as a voice of disenchantment, and Peter Sloterdijk, as a voice of enchantment.

1

It will be helpful to get a fuller picture of the enchantment Weber was talking about. For this I turn to Egil Asprem’s lengthy study, The Problem of Disenchantment (2014), which explores the various ways in which many thinkers have sought to keep some enchantment – some sort of magic – in their views of the world. Asprem’s study shows that magical thinking was not simply done away with in the course of what’s called “the scientific revolution” in early modern Europe. The story, as anyone would expect, is more nuanced and complicated. In trying to provide an accurate-enough picture for our purposes here, I would like to make three points.

First, there is a direct and easy way in which early modern philosophy was indeed at war with magic and enchantment. This can be seen in nearly every thinker’s concern over this period to do away with so-called “occult properties” and to find some way to replace them with bona fide physical properties. Descartes, Hobbes, and Gassendi audaciously claimed that all natural phenomena could be explained in terms of geometry and a simple set of laws of motion and impact, thereby clearing out strange, occult properties from their ontological inventories and overcoming scholastic metaphysics. One can also read Locke’s treatment of so-called secondary properties as an attempt to shore up human experience with a vaguely Cartesian model of physics (though, as usual, Locke’s cheery attempt raised far more questions than it answered, questions that sent Berkeley down his own path). Overall, the central theme of early modern metaphysics was to describe a natural world in which magic played no part; indeed, I would go so far as to say that “disenchantment” was the main thrust of early modern metaphysics.

First, there is a direct and easy way in which early modern philosophy was indeed at war with magic and enchantment. This can be seen in nearly every thinker’s concern over this period to do away with so-called “occult properties” and to find some way to replace them with bona fide physical properties. Descartes, Hobbes, and Gassendi audaciously claimed that all natural phenomena could be explained in terms of geometry and a simple set of laws of motion and impact, thereby clearing out strange, occult properties from their ontological inventories and overcoming scholastic metaphysics. One can also read Locke’s treatment of so-called secondary properties as an attempt to shore up human experience with a vaguely Cartesian model of physics (though, as usual, Locke’s cheery attempt raised far more questions than it answered, questions that sent Berkeley down his own path). Overall, the central theme of early modern metaphysics was to describe a natural world in which magic played no part; indeed, I would go so far as to say that “disenchantment” was the main thrust of early modern metaphysics.

But my second point is that, in every case, magic keeps creeping back into the story. Descartes was a dualist, and a Catholic, and it is hard to see how his metaphysics could possibly work without these magical elements added in. Locke connected ideas of secondary qualities with the sets of qualities causing them by simply declaring that, somehow, “God does it”, and Berkeley and the occasionalists had God’s miraculous actions implicated in every single worldly event. Even Newton, who is sometimes held up as the great disenchanter, refused to provide any natural account of action at a distance, and it was impossible for anyone at the time to see gravity as anything other than an occult property. (One can also add here that Newton’s dedication to alchemy and Biblical prophecy dwarfs his dedication to naturalistic physics, at least if we measure dedication by word count.) Each philosopher had, on the one hand, a no-nonsense basis from which to launch explanations, and, on the other, the wild bouquet of experience that needed to be explained, and the two never met up very well; and magic rushed in to fill the gaps. Hume drove this point home when he argued that causality itself is an occult property, perfectly opaque to any rational analysis. So if early modern philosophy aimed at disenchantment, it failed in this mission spectacularly and completely. (This second point, that magic always finds a way, is one of the core themes of Asprem’s wide-ranging book.)

My third point is a deeper and more troubling one. The great systems of philosophy, beginning with Descartes and extending up to Nietzsche, all carried with them a kind of enchantment that is inherent to constructing philosophical systems. This is what Nietzsche had in mind when he quipped, “I distrust all systematizers. The will to a system is a lack of integrity.” Philosophical systems are announced from a perspective that Thomas Nagel has called “the view from nowhere”, or an objective, unbiased perspective that is supposed to be underwritten by the authority of reason. But at the same time, these systems also provide, at least implicitly, a set of values about what we should be paying attention to, or how we should be living, or the attitude we ought to take toward our experience.

My third point is a deeper and more troubling one. The great systems of philosophy, beginning with Descartes and extending up to Nietzsche, all carried with them a kind of enchantment that is inherent to constructing philosophical systems. This is what Nietzsche had in mind when he quipped, “I distrust all systematizers. The will to a system is a lack of integrity.” Philosophical systems are announced from a perspective that Thomas Nagel has called “the view from nowhere”, or an objective, unbiased perspective that is supposed to be underwritten by the authority of reason. But at the same time, these systems also provide, at least implicitly, a set of values about what we should be paying attention to, or how we should be living, or the attitude we ought to take toward our experience.

2

I would like to illustrate this by considering a contemporary attempt at thorough philosophical disenchantment: Daniel Dennett’s naturalism. Dennett is a student of Quine, and like Quine he eschews “first philosophy” (or a priori metaphysics) and takes philosophy’s job to be, basically, using current science to answer or to debunk traditional metaphysical questions. Another way to put it is that Dennett is waging a campaign to thoroughly disenchant philosophy, and to suck out any magic that has crept in to fill the explanatory gaps.

See, for example, Dennett’s TED talk, “The Illusion of Consciousness”, especially from 5:09 – 7:10:

Still another way to characterize Dennett’s philosophy is that he is trying to deprive philosophy of any domain of inquiry that belongs specifically to it, as opposed to science. This is the main reason, I think, that many professional philosophers don’t like Dennett: he cedes all of philosophy’s domain to the natural and social sciences, and philosophers are left doing the clean-up work of explaining exactly how traditional philosophical problems are either answered or dissolved through naturalized inquiry. If philosophers insist on the irreducible nature of qualia, for example, or of contra-causal free will – let alone any variety of theism! – Dennett will quickly accuse them of magical thinking, and offer an explanation of how a smart, well-intentioned person might end up believing (but believing falsely) in such irreducibility. The basic outlook is that, if it isn’t science, then it is something to be explained through a weakness in human psychology (and so in that way it turns out to be science after all). As Dennett insists, there never is any magic.

This might sound like a criticism of Dennett – but in fact I think that his enthusiasm for debunking (what I call his “dansplaining”) grows from deep philosophical roots going back to Thales and Socrates. There is a long, long tradition of philosophers not getting on well with religionists and poets, faulting them for giving in to magical thinking and for not subjecting their beliefs or their utterances to rigorous cross-examination. No philosopher likes being accused of magical thinking; any philosopher accused of it will deny the charge and restore their credibility by insisting that the natural domain, in their view, just has more stuff in it than someone like Dennett believes there to be. In this, they assert themselves to be naturalists, and not supernaturalists. Harkening back to Weber, we can say that, to a philosopher, intellectual integrity is everything, and no one is willing to make the sort of intellectual sacrifice Weber thinks has to be made if one wants to be both enchanted and a scientist. Dennett’s philosophy, and the dialectic between him and his critics, shows that there is a powerful drive in philosophy toward disenchantment.

But if we recall the second point I made regarding Asprem’s book – namely, that magic always finds a way to creep back in – then we might well ask in what way Dennett’s project is compromised. I believe the compromise is made at the very foundation, in Dennett’s scientism. While Dennett cheerfully deconstructs the belief systems of qualia freaks and other fantasists, he shows no interest in deconstructing science (and philosophy) as a human institution, subject to cultural, economic, and political pressures. He’s not interested in disenchanting our faith in science, and instead accords it an epistemic privilege rather like the privilege the astrologist extends to the stars.

So, for one example, no philosopher to my knowledge has made the connection between the Turing test (and, later, Searle’s Chinese room) to the Red Scare of the 1950s and 60s. The historian Simon Schaffer has recently done so, in a fascinating lecture on Turing’s imitation game and the film The Manchurian Candidate. In this lecture Schaffer brilliantly illuminates why intellectuals of that time would be so keenly interested in the phenomenon of an agent “passing” as someone they are not, as well as the darker secrets of the human mind: think of double agents, and the defense industry’s interest in mind control, mesmerism, and hypnosis. (Think here more generally of Men Who Stare at Goats (2009).) These ambitious projects in the Soviet Union, China, and the US were founded on a deep paranoia of an agent not being what he or she offered themselves as. Turing extended this into the realm of machines and human agents, wondering whether machines can think and, implicitly, whether humans may be programmable machines. To explore the Turing test without paying some attention to the historical circumstances surrounding it – and, by the way surrounding us still today, in the age of cyberattacks and AI – is to pretend that the world of philosophy (and science) is insulated from a broader context of historical conditions. That, I shall submit here without argument, is magical thinking of a very advanced degree. Science is a human endeavor, after all, and as Kant observed, from the crooked timber of humanity nothing straight was ever made.

What I am claiming here is that Dennett might be located at the “disenchanting” end of the spectrum, but even he does not go as far as he might. He retains scientific inquiry as a kind of skyhook for his dansplanations, and does not press into the ways in which natural science might be historically naturalized. Furthermore, I suppose someone who took this additional step might also have to go even further, and inquire into the ways in which historians themselves are subject to political, professional, and cultural pressures. One one sets of down the path of disenchantment, one will find no natural resting place: it is critique all the way down, so to speak, with every alleged “view from nowhere” being relocated as a view from an identifiable time and place, politics and class. This pursuit puts us in the company of Foucault, in whose company a great many contemporary philosophers do not find comfort.

This criticism of Dennett also points vaguely toward the way in which more sophisticated attempts to find grounding for human value also have their own magical elements. I have in mind efforts, inspired by Hegelian philosophy, to explain our values as social constructions. According to these efforts, any society has its values as the result of a long and complicated history. Values do not drop from the sky, or bubble up through some special moral insight we call “moral intuition” – these are both obviously magical accounts of value – but instead are constructed in real time through legislation, the creation of institutions, and the results of public discourse and – yes – philosophical dialogue. This long and complicated history can be discovered and made explicit by engaging with empirical history, political science, sociology, psychology, and evolutionary psychology. (This, in fact, was Weber’s own lifelong project.) Anyone who does a thorough job of putting this story together should also, of course, consider ways in which the historical accounts might themselves be skewed by the cultural optics of the day.

But in the end, what results from these Hegelian efforts? We either end up with a sober, relatively value-free account of the history of socially-constructed value – basically, the story a cultural anthropologist might tell of the evolution of curious belief systems of homo sapiens – or we find some way to convince ourselves that these social constructions of value have some directedness to them, or some sort of teleology that guides the constructions in a way that lends them special legitimacy. (In short, we drink the Hegelian Kool-Aid.) When we are inside those value systems, so to speak, we can get on with the business of moral discourse and debate – and I do not wish to deny that that is good and meaningful work. But being inside means ignoring for the moment the contingent and arbitrary nature of the factors that shaped our systems of values. If we try to step outside those systems of value, assuming the position of the Martian observer, we find ourselves once again in the disenchanted world Weber described as the domain of genuine science. We can’t both know the story of the construction of value and at the same time take that value as valuable. That is yet another way of putting the point Weber was making.

So, to sum up, I am arguing (or really only gesturing toward an argument) that philosophy, when thoroughly pursued in a familiar, Dennett-esque fashion – that is, in a Weberian scientific fashion – ends in disenchantment, and retaining any confidence in our values would require the sort of intellectual sacrifice Weber described.

3

At this point I would like to shift toward a very different conception of philosophy. According to this alternative conception, philosophy’s job is not to disenchant, but rather to provide some sort of enchantment which might give human beings a kind of direction and purpose after having traveled down the long, descending road of disenchantment. And so I turn to Peter Sloterdijk.

[Obviously, on this blog I have expressed plenty of my mad enthusiasm for Sloterdijk. Rather than rehearse everything here again, if you are interested and haven’t seen it already, you might see my discussion here.]

[So: … spheres … shared interior… bell jar of purpose …etc, etc]

To point out the obvious, Sloterdijk’s vision of philosophy and enchantment is the complete reverse of what Dennett supposes. Dennett sees enchantment as a disease to quarantine and eradicate; Sloterdijk sees it as a sort of medicine which, when intelligently applied, can save us from the despair of our own self-knowledge. For Sloterdijk, philosophy ought to be in the business of generating some form of enchantment, for the disenchanted life is not worth living.

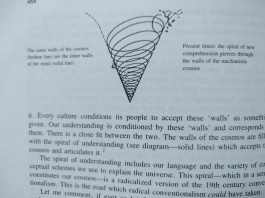

These two very different modes of philosophy ran up against one another in a memorable exchange in The Library of Living Philosophers volume on Quine. The editors included an essay by a philosopher who chastised Quine for not being concerned with the great big philosophical questions of consciousness and meaning and humanity. He wrote about human consciousness spiraling outward against the great walls of the cosmos in its attempt to formulate a great conception of meaning – even providing a diagram! – and he predicted that Quine would pretend not to know what he was talking about. In his reply, Quine answered, “I am perversely tempted to pretend I do know what he is talking about. But let us be fair; if he claimed not to know what I was talking about, I would not accuse him of pretending.” It is, in its own way, an amusing slapdown (and I suspect the editors invited this contribution precisely to afford Quine the chance to dish up such a mean-spirited reply). But I think it is also significant and revealing. To put the point somewhat magisterially, the disenchanted philosopher knows not what the enchanted one says, and the enchanted one can only accuse the disenchanted one of pretending not to know.

These two very different modes of philosophy ran up against one another in a memorable exchange in The Library of Living Philosophers volume on Quine. The editors included an essay by a philosopher who chastised Quine for not being concerned with the great big philosophical questions of consciousness and meaning and humanity. He wrote about human consciousness spiraling outward against the great walls of the cosmos in its attempt to formulate a great conception of meaning – even providing a diagram! – and he predicted that Quine would pretend not to know what he was talking about. In his reply, Quine answered, “I am perversely tempted to pretend I do know what he is talking about. But let us be fair; if he claimed not to know what I was talking about, I would not accuse him of pretending.” It is, in its own way, an amusing slapdown (and I suspect the editors invited this contribution precisely to afford Quine the chance to dish up such a mean-spirited reply). But I think it is also significant and revealing. To put the point somewhat magisterially, the disenchanted philosopher knows not what the enchanted one says, and the enchanted one can only accuse the disenchanted one of pretending not to know.

The two philosophical approaches also differ fundamentally in what sort of discipline they conceive philosophy to be. For Dennett, student of Quine, philosophy rides piggy-back on science, and the presuppositions it carries are the same as those of science. For Sloterdijk, philosophy is a profoundly humanistic affair, drawing upon history and literature as well as art and architecture in its assessment of where we are and where we should be going.

Just as we saw that, in the case of Dennett, there is something to be said for seeing philosophy as driving toward disenchantment – for most philosophers do not wish to be accused of magical thinking – we must also admit that there is something to Sloterdijk’s vision as well. In its most widespread and popular sense, philosophy presents an encompassing vision through which individuals can not only make sense of the world, but can also find some place for meaningful endeavor. Plato’s form of the good, Aristotle’s account of virtue, Descartes’s Catholicism, Spinoza’s single-substance doctrine, and Kant’s noumenal world are integral parts of their attempts to retain some sort of enchantment in the world. Even Dennett’s expression of wonder over the workings of nature – the delight he finds in his own dansplanations – is a low-octane form of enchantment, and it provides the foundation for what he regards as a human life worth living. Are these instances in which philosophy has failed in its job to shake off all enchantments? Or are they instances where philosophy has successfully done its job, generating the enchantment we need in order to live with ourselves?

I regard this as a profound philosophical question – which is to say, I have no intention of trying to answer it. It seems to me that, yes, philosophy must interrogate ruthlessly, with the aim of exposing the weak points in our explanations and the points at which we give ourselves over to magical thinking. And it seems to me that, yes, philosophy should provide direction and purpose for human beings, and that Weber’s so-called “problem of disenchantment” is a genuine problem for us that we should strive to answer. So I wish both Dennett and Sloterdijk well, and cheer them on in their efforts. But I do worry – and pardon me here for getting a little preachy – about many of us trying to have it both ways, and thus unwittingly making the intellectual sacrifice Weber describes. It is very easy, in any field of contemporary scholarship, to get lost in the weeds, and not realize either that we are drawing upon sources of enchantment to which we have no legitimate access, or that we are not recognizing the inhuman, unlivable aspects of the paradigm in which we are working. In other words, we may be engaging in magical thinking without realizing it, or we may be actively contributing to a vision of human life that is deeply problematic, at least for those who want to try to live it. Philosophy, no doubt, is an extraordinarily difficult task, and perhaps it cannot be practiced fully and completely without some degree of intellectual sacrifice. Perhaps the examined life requires an unexamined component. That, I suggest, is a paradox well worth thinking about.

Leave a comment